The projector flickered. The AC hummed louder than the confused murmurs in the room. Aman had just raised his hand with a frustrated sigh and said what I’d been waiting for all week: “Sir, I declared a variable inside a function and tried to use it in another… but it says ‘undeclared identifier.’ Why can’t C see it?” That was it. The perfect crack in the wall. The precise moment to introduce one of the most fundamental but misunderstood concepts in programming: Scope.

When the Variable Is a Secret

I walked over to the whiteboard and drew a big rectangle.

“This is your house,” I said.

Then I drew three smaller boxes inside kitchen, bedroom, bathroom.

“If you leave your toothbrush in the bathroom,” I asked the class, “can you use it from the kitchen?”

Riya immediately said, “Unless you shout to someone to bring it!”

Exactly.

That’s how I begin my lecture on Scope with the idea that a variable lives in a specific room (a function or a block), and unless you pass it out or declare it in the hallway (outside all rooms), you’re not going to be able to access it from another.

Let’s take a real example:

int global = 10;

void show() {

int local = 5;

printf(“%d\n”, global); // OK

printf(“%d\n”, local); // OK

}

int main() {

printf(“%d\n”, local); // ERROR: local is not declared here!

}

What is Scope, Really?

Scope isn’t some abstract idea. It’s real. You can feel it when your code breaks, and a perfectly good variable becomes invisible.

During my lectures, I say:

“Scope is like the life and visibility of a variable. Where it lives, where it can be seen, and when it dies.”

The scope of a variable determines two things:

- Where in the code you can access it.

- When it is created and destroyed (its lifetime).

Let’s go back to the toothbrush analogy:

- If you declare a variable inside the bathroom, it stays in the bathroom.

- If you declare it in the living room (outside any specific function), anyone in the house can use it it’s global.

The Big Two: Local and Global Variables

Every semester, I break it down like this:

🔹 Local Variables

- Declared inside functions or blocks (like main() or loops).

- Created when the function starts, destroyed when it ends.

- Not visible outside the block they’re declared in.

I remember once a student tried to print a variable declared inside an if statement from outside it.

if (1) {

int temp = 50;

}

printf(“%d”, temp); // Error!

“Sir, but I just declared it! It should be there.”

I smiled. “It was there. But that if block was its room. The moment that block ended, the variable was erased like it never existed.”

We even had a little ritual where I’d write a variable name on the board, then erase it dramatically after the function ended. Students laughed, but they never forgot again.

Global Variables

- Declared outside any function.

- Alive from the start of the program to the very end.

- Accessible from any function.

int counter = 0;

void increment() {

counter++;

}

When I showed this in class, it clicked for many students who had previously struggled with passing values between functions.

One student said, “So a global variable is like a whiteboard outside the classroom. Anyone can write or read from it.”

Perfect metaphor. But I also warned them…

“Global variables are powerful but dangerous. Use them with caution. Too many global variables, and your code becomes a maze.”

Nested Blocks and Visibility

Now here’s where it gets interesting. I usually draw a big curly bracket on the board, then a smaller one inside it.

int main() {

int a = 5;

{

int b = 10;

printf(“%d”, a); // Accessible

}

printf(“%d”, b); // Error: ‘b’ not declared in this scope

}

I ask: “Why can we access a inside the inner block, but not b outside?”

Silence.

Then I explain:

- Inner blocks can see the outer ones.

- Outer blocks cannot see into inner blocks.

Think of it like being in a company:

- An intern can see the company rules (declared globally).

- But the CEO doesn’t see the intern’s private notes unless they’re shared.

One of my favorite moments came when a student summarized it in their own words:

“Sir, so it’s like light: it flows inward, but doesn’t shine back out.”

Exactly.

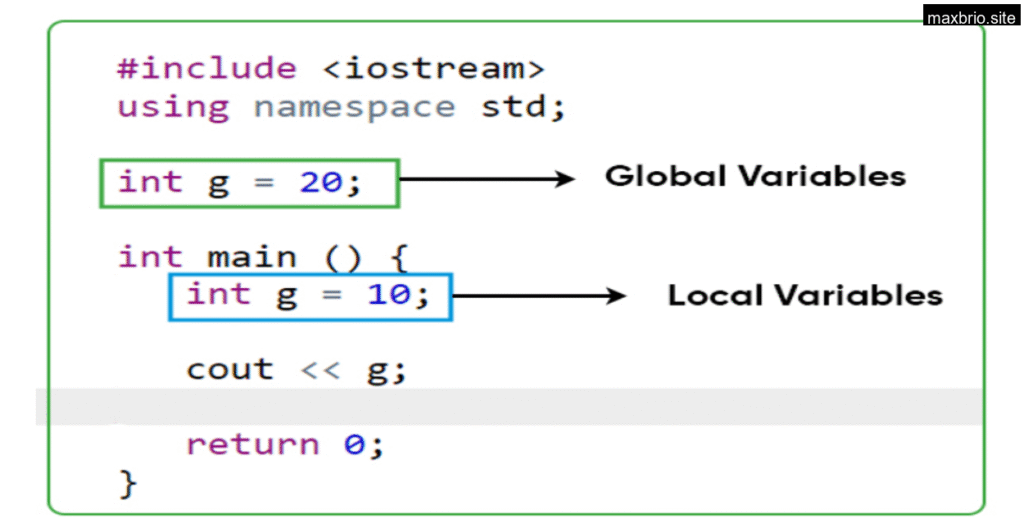

Variable Shadowing The Tricky Part

Here’s where even the sharpest students sometimes stumble.

int var = 10;

int main() {

int var = 5;

printf(“%d”, var); // What gets printed?

}

Answer: 5.

“But sir, isn’t 10 the global value?”

I love this question because it helps me introduce variable shadowing. When a local variable has the same name as a global one, the local version hides or shadows the global one in that scope.

“Local variables are like a fog. You can’t see through them to the global ones.”

But once that function ends, the fog clears, and the global is visible again.

Memory and Lifetime: When Do Variables Really Die?

Once, a curious student asked, “Sir, where do these variables go when they die?”

A little morbid. But technically interesting.

So I explained the stack and heap with a metaphor.

I said:

“The stack is like your exam desk. You keep your current question paper on it. When you’re done, you tear it and throw it. Local variables live here. The heap? That’s like your bag things stay there until you decide to clean it.”

Local variables live on the stack. They are created when the function starts and destroyed when it ends. That’s why the same function can be called multiple times and the variable starts fresh each time.

Global variables? They live throughout. Their life begins when the program starts and ends only when the program does.

Why Scope Matters (More Than You Think)

I once walked into a debugging session where half the lab was stuck on a mysterious error. They had reused the same variable name in multiple places and kept getting “unexpected results.”

I opened their code, scrolled for a few seconds, and then said:

“You’re using the wrong ‘x’. You declared one inside the loop and another outside. You’re printing one and changing the other.”

They blinked.

That’s when I realized: Understanding scope is the difference between writing code and writing correct code.

Scope and Functions: A Dance of Access

We later experimented with writing our own functions. Some students declared everything inside main() and tried to use them in fun().

void fun() {

printf(“%d”, val); // Error!

}

int main() {

int val = 42;

fun();

}

“Sir! But val is declared!” they’d say.

Yes but not in fun().

It’s like trying to use a friend’s Netflix account without their login. If you want to share, you have to pass it via parameters.

Or you can make it global but then anyone can mess with it.

That’s why I tell them:

- Use local variables for safety.

- Use global variables for shared state but sparingly.

When in Doubt, Ask: Where Was It Declared?

One of the best debugging habits I try to instill is this:

“When a variable misbehaves, first ask: Where was it born? Where does it live? Where does it die?”

That simple reflection solves 90% of scoping issues.

Final Word: Scope Is Respect

Scope is not just a rule. It’s a principle of respect.

A variable lives in a block. That’s its home. Don’t expect it to come out unless you’re explicitly passing it around. Don’t shout from one room to another hoping someone hears you.

As I always end this topic:

“Respect the boundary. Understand the scope. Your code will be clearer, safer, and easier to debug.”

Can a local variable have the same name as a global one?

Yes. The local one will shadow or override the global one within that block.

Why does my function not see a variable declared in main()?

Because main() is a separate block. Variables declared inside main() are local to it and not accessible from other functions unless passed as parameters.

Are global variables initialized by default?

Yes. Global variables are automatically initialized to zero if not explicitly given a value.

Can we access a variable from an inner block in the outer one?

No. Variables declared inside a block are not visible outside of it.

What is the best practice local or global variables?

Use local variables by default. Use global variables sparingly and only when multiple functions need shared access.